The Change Perspective

Adapt or Die!

Like other organisms, organisations must continually reinvent themselves to survive and thrive. With the accelerating pace of change, the ability to rapidly evolve has become an existential necessity. Agility is required not just for teams but also at an organisational level.

ELSE is a continuous improvement approach that fosters emergent practices, guided by actionable principles, to enhance organisational agility at scale.

Those organisations that can’t or won’t adapt are destined to decline and go the way of the dinosaurs. Some organisations will change just fast enough to survive, whilst others won’t just respond, their ability to innovate their products and capabilities will create a competitive edge and contribute to the pace of change. Leadership has a fundamental responsibility to help unleash their organisation’s human potential to continually out-learn and out-adapt competitors. Any scaling endeavour will require adaptation from current structures, behaviours, systems, processes, policies, etc., to an organisation better equipped to thrive in its ecosystem.

The ability to continually change must be incorporated into an organisation's DNA rather than treated as a transaction with a beginning and end. It will likely be too late if an organisation waits until an event makes the need for change evident.

Organisations need to adapt, but in which direction? Simply copying “Best Practice” from other organisations is unlikely to create a competitive advantage, and there is no guarantee that it will suit your unique organisational context and culture. Leadership takes responsibility for catalysing a direction and purpose for change that guides a process of emergent practice.

"It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change." Charles Darwin (1809 - 1882)

Challenges to Change

Changing organisational systems is generally challenging, highly disruptive, risky and takes more time than expected. The larger the change and the greater the cultural shift required, the more this is true.

Many personal, group and systemic factors push back against proposed changes. Some of these are illustrated above and are discussed further below:

- Ingrained Habits - Habit creates inertia to change; by default, people will do things the way they always have.

- Fear of Change - Change is complex and uncertain, creating a fear of the learning challenge and potential negative impacts on those involved.

- Size and scope of Change - More dramatic changes and those impacting more people and systems will suffer increased resistance.

- Risk of Change - Some changes have a greater perceived or real risk of high-impact failure.

- Difficulty of Change - The proposed changes may require new or rare skills, or organisational support capabilities that are immature or yet to be implemented.

- Lack of Motivation - The need for change has not been widely established and communicated or belief and trust in the proposed changes are lacking.

The approach to change has to address these challenges to have a chance of success.

Evolutionary and Emergent Change Model

The “Change Journey” is at least as important as where you arrive. A transactional change from today’s state to a target state misses out on the journey experiences and learnings, which provide time to learn, adapt and acclimatise.

Organisations are complex adaptive systems by nature, and changing a sociotechnical system is an inherently difficult and unpredictable business, often resulting in unforeseen side effects. Designing an ideal comprehensive target model for your change and then performing a transactional transition is destined for failure.

Agile approaches have emerged to deal with complex problems, so they are a natural choice to apply to the challenge of change. ELSE offers an evolutionary and incremental change model, with inspection and adaptation cycles at its heart.

Supporting Principles:

The ELSE Change Model is illustrated below. The outline of the change cycle is modelled as an outer OODA loop that uses ELSE Actionable Principles to help guide where change is required and in which direction. An inner OODA loop models the Experiment and Learn cycle to emerge and establish new practices.

Catalyse Purpose!

Given the challenges of change, there needs to be clear and agreed reasons that will motivate people to risk modifying systems and ways of working. Clarity of purpose will also inform strategies and decisions on the direction and detail of the evolving changes.

At a high level, the need to continually evolve the organisation to stay relevant and viable will likely be a constant but abstract motivator. As we go deeper, more specific and concrete reasons for improvement to systems, processes, policy, etc. will need to be established. These purposes must be formed in collaboration with those involved and impacted by potential changes. The alternative, the top-down imposition of purpose, is unlikely to have the necessary ownership and buy-in and could lack essential input from diverse perspectives. See “Engage People” below.

Supporting principles:

Observe

When reviewing the root causes of change failures, it is common to find faulty assumptions and incomplete perspectives of how complex work gets done. It is easy to miss many informal networks and relationships and put too much trust in official documentation and organisational structure.

We must start changing from where we are, with an honest and critical analysis of the current system of work with a mindset to discover, drill down and address root causes of challenges to value creation.

Engage People

Involve those affected by change in exploring the current systems and processes and identifying opportunities to improve them. This strategy will lead to better-informed change with buy-in and increased motivation from those who will enact the improved processes.

Many change programmes meet significant resistance from those impacted by the change. One of the reasons for this resistance is that the change is forced on them, and they lack understanding of the reasons driving the change. Establishing the “Why” through collaborative engagement with those impacted by change can shift their place in the change process from victims to supporters.

Process changes are often designed based on flawed assumptions about current processes. Involving those with intimate knowledge of systems and processes impacted by change leads to better-informed decision-making. In addition, ensure that we ask “What assumptions are we making?” to ensure that assumptions are explicitly recognised so that we can decide how best to validate or invalidate them. This, in turn, increases trust and helps reduce resistance to change.

Supporting principles:

- Involve those affected by change

- Shared context improves decisions

- Maximise engagement

- Create clarity of purpose

- Catalyst for change

Create Safety

Amy Edmondson defines Psychological Safety as ”a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes…”

It seems such a simple statement, but without Psychological Safety, nothing good happens: errors and issues remain hidden, and learning and improvement are stunted. With high levels of Psychological Safety, we open the door for greater engagement and innovation, improved work quality and collaboration, and support for learning and process improvement.

Establishing a safe environment is a priority for leadership to ensure that less bravery is required to identify and explore current challenges down to their root causes. A reduction in the “fear of failure” will enable experiments to safely explore innovative solutions and identify and apply learnings.

Allow people to commit, rather than being committed to a change. Seeking volunteers for experiments increases engagement and empowerment, as well as ensuring that there is motivation to trial an experiment fairly.

Supporting principles:

- Create the environment for people to thrive

- Foster a high trust environment

- Involve those affected by change

- Maximise engagement

- Create a Learning Organisation

- Evolutionary over revolutionary change

Map Context

This step aims to establish a shared understanding of the current context by engaging all relevant stakeholders and sources of data in a rapid, collaborative process. Avoid getting bogged down in over-analysis and ensure that all stakeholders appreciate that this is an emergent process.

Structured interactive workshops are an excellent approach to engage and incorporate diverse perspectives into a shared picture of the current context and surface the challenges to address.

There are many workshop techniques and structures that can be used, Value Stream Mapping is an excellent example. Whilst deriving ELSE, we evolved an effective Context Mapping Workshop (this will be documented in the Practices section of the wiki), which is another option.

Here are some ideas for workshop options to support the mapping of the current context, digging down to root causes, and assessing the strengths and weaknesses of potential improvement options:

- Value Stream Mapping

- Impact Mapping

- Wardley Mapping

- Causal Loop Diagramming

- Fishbone Analysis

- 5 Whys

- Forcefield Analysis

Orient

Orient is primarily a “divergent” activity, making sense of the observations and generating diverse options whilst delaying commitment to a specific way forward.

Inspect with ELSE Principles

“If you only have a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.” Abraham Maslow

Best practices and patterns are typically the “hammer” resulting in a poor fit to specific organisational contexts. We must work a little harder and apply principles that can inform the emergence of better practice that is appropriate for the current context. Given that the context will change, this has to be a repetitive cycle of evolutionary change.

With a comprehensive map and understanding of the current context, inspect with common sense and the ELSE Principles as lenses. Identify where there are larger gaps between the principles and reality, pointing to opportunities for improvement.

With the application of the collective diverse perspectives of stakeholders, the mapping exercise often reveals previously hidden challenges. Others require the application of the principles as their impacts may be harder to spot or pin down the causes.

Use the ELSE Principles to inspect the map(s) and explore how the current context supports each principle. A useful workshop technique is to divide stakeholders into small groups, each applying a subset of the principles for a time-boxed period before rotating to another subset.

The outcome should be a list of areas for improvement that can be ordered by impact.

Identify Options

With the ordered list of improvements as input, engage stakeholders to generate multiple diverse options for improvement experiments.

Focus on scaling “Value” rather than assuming the need to scale the size of the development system. First consider “De-scaling” by exploring options that enable the scaling level and complexity to be reduced. A surprising amount of performance improvement can often be unlocked by reducing complexity and overhead. For example, team performance often suffers from interdependencies that cause delays and prevent completion of work. We could choose an option to add additional meetings to manage the dependencies, or we could look to reduce the dependencies by simplifying the product and team structures.

Supporting Principles:

- Involve those affected by change

- Scale only when you need to

- Start small and scale success

- Minimise unnecessary complexity

- Committed to required structural changes

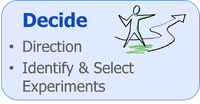

Decide

Direction

To quote Dave Snowden “In complexity, you describe the present and see what you can change. You define a direction of travel, not a goal.”

So, instead of a future end state, we define how we will recognise whether we are making improvement. This direction of travel then provides context for selecting experiment options that appear to be good bets.

Identify and Select Experiments

Limiting the scope and framing changes as experiments rather than finalised change decisions reduce fear and risk. Work to reduce the scope of changes so that they impact only a small part of the system’s processes and a manageable subset of people.

Start small with the primary objective of maximising learning - validating or invalidating assumptions and risks, and gaining empirical data that enable better planning and decision-making for the next steps.

When selecting options, it is worth considering addressing challenges considering the emphasis shown in the diagram below:

We see many instances where team structure and communication patterns are optimised within a poor product structure and product ownership that reduces their alignment with value creation. So whilst tactical improvements can be accomplished at a team level, greater progress may require starting with improvements to the structure of products and services before addressing product ownership and teams.

Don’t assume the need to scale! Consider that you might not need to scale at all: a highly productive team working in a supportive environment might be everything you need to create great products. Scaling always adds complexity and process wastes, so prioritise options that improve at the current scale before resorting to scaling.

Options can be assessed and prioritised by many factors, including:

- Positive impact

- Financial cost

- Effort

- Availability of required skills or capability

- Availability of willing volunteers

- An event that provides context and motivation

- Risk and blast radius

- Resistance

- Elapsed time to feedback and learning

Supporting Principles:

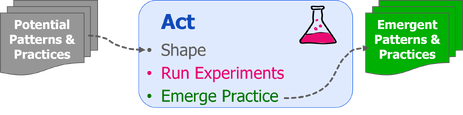

Act

It is now time to shape, initiate and support the experiments in an incremental cycle. Framing changes as experiments provided the safety to ”fail” and learn as a natural part of complex change where outcomes are not certain and failure should be expected. Even successful experiments will have lessons and improvements emerging from them. Successful Emergent Practice can be shared and experimentally broadened as appropriate.

Shape Experiments

Intentionally frame potential changes as “Experiments” to ensure that we are admitting that we don’t know everything and the outcome is by no means certain, with “Failure” a likely option. Make it “Safe to Fail” by reframing “Failure” as “an unexpected outcome of the experiment that provides an opportunity to learn”. The learning can then be incorporated into improved or illuminate better alternative change options. This strategy reduces the traditional stigma of failure that creates a fear of innovating and changing the way things have always been done.

Collaboratively develop a hypothesis for an experiment to address an option for improvement. A change experiment hypothesis may include the following elements:

- The “Why” - context of the challenge to the Scaling principles.

- The outcome we hope to see.

- Experiment plan outline

- When - how long we expect to run the experiment and observe results.

- Who - people involved and impacted.

- What changes - structure, systems, processes, policies, skills, roles, etc.

- Validation - how we will assess outcome progress and success.

- Key assumptions, challenges and risks.

- Support required.

Shape small experiments, or as Jason Little refers to them: MVCs - Minimum Viable Changes. When considering what to change - keep impact and effort low by making local and/or temporary changes or exceptions to normal working practices for the experiment timebox. If the experiment validates changing more officially and widely, then see Start small and scale success.

Patterns and Practices as an input

Practices and patterns harvested from external sources such as scale frameworks and other organisations are useful input, they should be adapted to fit the specific context. Practices are then “Emerged” through a process of evaluating, learning and further adaptation based on the outcomes of small experiments.

Shaping Parallel Experiments to Speed Learning

Intentionally running parallel experiments can enable more learning in a given period of time. However, there are some caveats:

- The experiments must be able to run independently without impacting each other and this might be difficult to predict. It must be possible to attribute observed outcomes to a specific experiment and avoid the possibility of one cancelling the benefits of another.

- Ensure that the additional WIP due to initiating, supporting and learning from the experiments does not negatively impact the outcomes of the process. Taking on too many parallel changes can overload the capacity to support the experiments and may lead to incorrect invalidation of good ideas that lack sufficient support.

Supporting Principles:

- Involve those affected by change

- Foster a high trust environment

- Committed to required structural changes

- Provide an impediment removal service

- Catalyst for change

- Create Clarity of Purpose

- Limit Work In Progress

Run Experiments - Observe

Support

Without support, many experiments are destined to wither and die before they can provide learning or change. Leadership keeps momentum for change by ensuring continued focus on improvement as part of day-to-day work and reducing the friction caused by the existing environment.

It is often necessary for leaders with sufficient seniority to provide the authority to bend or break the current formal and informal rules and processes. In addition, it is easy for experiments to lose their way and regular restating and reinforcement by leadership of the purpose and intended direction of travel provide the stability of intention.

Those in leadership or influential positions can support experiments in the following ways:

- Regularly refresh and reinforce the purpose to keep aligned on the “Why”.

- Provide air cover to enable bending or breaking of normal rules within the context of the experiment.

- Create enough time to trial new ideas. Many changes fail simply due to delivery pressure and focus.

- Help understand and mitigate or resolve impediments.

- Support a “Safe to Fail” culture by ensuring that responses to unexpected outcomes of experiments are constructive and lead to learning and adaptation.

Prompts and Triggers

Even with great motivation to change, there is the inertia of ingrained habits to overcome. To help tackle this challenge to change, we need to provide some scaffolding to initiate new behaviours. If we don’t plan to work differently, we will carry on in the same way and nothing will change! An effective pattern is to either modify or insert prompts into existing processes and systems to trigger new behaviours. For example, a change might be as simple as adding a new column to a Kanban board or inserting a question into a planning meeting agenda.

Skills and Capabilities

Address shortcomings in the skills and capabilities of people and systems in order to reduce the challenge of the new behaviours. If a change is too difficult, people will be far less likely to follow through. Furthermore, supporting the professional growth of the people will help in keeping them engaged with the change process.

Culture Impact

Organisational culture is notoriously difficult to influence directly. Initiatives to improve culture almost always fail. Culture is an outcome of the way we work, so by using experiments to gradually change how work is done, indirectly impacts culture.

From John Shook’s work and learning from his NUMMI experience (https://www.lean.org/downloads/35.pdf), we know that behaviour drives culture, values, attitudes and thinking rather than the traditional idea of teaching people new ways of thinking first.

An experiment that incorporates new or changed behaviours, processes, systems, artefacts or environmental context, is likely to evolve the culture of those impacted. As a successful experiment is adopted more broadly the breadth of the cultural impact also increases. So, changes made to the working environment and its associated systems and processes will impact how people behave and think. This is clearly an essential element of the feedback loop into the process of emerging practice and cultural change.

Another relevant study revealed: “Environmental factors, which often seem benign or inconsequential, play powerful roles in shaping our behaviors.” - see The Good Samaritan Study.

Supporting Principles:

- Foster a high trust environment

- Committed to required structural changes

- Provide an impediment removal service

- Catalyst for change

- Create clarity of purpose

Gather Data

The purpose of an experiment is to learn and this requires that information is generated and harvested, regardless of whether the outcome was as expected. Unexpected outcomes often present the greatest opportunities for learning, as they can help us uncover faulty assumptions and gain new insights.

Orient

Analyse

When it comes to cultivating a Safe to Fail culture, asking questions like "What can we learn from this outcome?" helps foster open and honest discussions that are free from blame. In contrast, questions like "Who thought this was a good idea?" can be thoroughly counterproductive.

It is vital that the outcomes, whether intended or unintended, are investigated down to root causes (using the 5 Whys and other techniques) to ensure depth understanding, learning and adaptations that don’t just address symptoms.

Identify Options

Once we have established root causes and sufficient understanding, generate diverse options for improving the outcome. These may include options to refine the experiment and keep running it, adopt the experiment more broadly or abandon it and select another option entirely.

Decide

Based on what has been learned so far, decide on the best option to take the next step forward.

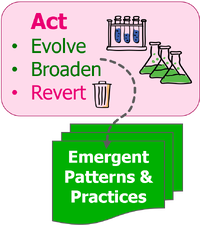

Act

Evolve and Broaden

It may be that we have now validated assumptions, derisked some key risks and provided the basis for understanding how we need to scale up and expand the teams. Alternatively, we are making excellent progress, so scaling is not required. Or, perhaps the “Start Small” approach has quickly and cheaply “Failed”, and the business can now make a better decision and pivot to an alternative strategy. The larger the scale, the more expensive and difficult it is to make the hard call to abandon a bad idea!

Supporting Principles:

Once experiments have reached a level of maturity where there is good evidence that the changes are positive and practical, then incrementally broaden through engagement with a wider scope and audience.

Scaling success should be carried out in an incremental and evolutionary style rather than a big-bang rollout! This process should still be “Experimental”, looking to learn and evolve, being considered “Emergent Practice” and definitely not “Best Practice”. Understanding the context of the successful experiment is vital when considering its broader application or incorporation into formal practices.

Seeking volunteers is always preferred over mandating and pushing changes onto unwilling victims! The guidance on engaging those impacted by changes still holds when broadening and evolving practice. Engaging volunteers from the initial experiments to act as supporting coaches for new groups can reduce cognitive load and speed up the evolution of improvements.

Supporting Principles:

- Start small and scale success

- Scale only when you need to

- Evolutionary over revolutionary change

- Involve those affected by change

Revert

Experiments must be allowed to fail as they will not always have positive outcomes or may come with unforeseen side effects. When this happens, implement actions to revert the experiment and celebrate the learning!

Emerge Practices

Whilst practices and patterns harvested from external sources such as scale frameworks are useful input, they should be adapted to fit the specific context. Practices are then “Emerged” through a process of evaluating, learning and further adaptions based on the outcomes of small experiments.

True innovative change often emerges from the serendipitous and accidental discovery of practices and patterns that provide both intended and unintended benefits and improvements. Of course, the reverse can also occur, with unintended and unforeseen negative side-effects resulting from an experiment.

Intentionally and regularly assess the results of experiments to understand the desirable and undesirable consequences arising. Analyse whether the consequences point to alternative purposes that were not originally envisaged i.e. intentionally repurpose existing and emergent capabilities for reasons that are different to the original intent. Dave Snowden refers to this process as Exaptation.

Actively look for and experiment with removing practices whose purpose appears to have become redundant but have been retained through force of habit.

Repeat!

Improvement is a continuous endeavour and should definitely not be considered a transactional process.

The impact of improvements will change the context, and given the complex adaptive nature of human systems, the outcomes may not be entirely as expected. It is, therefore, essential that we start by re-engaging our people to re-assess the context before embarking on further changes.

Change Perspective Summary

- The ability to continually change must become part of an organisation's DNA rather than being treated as a transaction with a beginning and end.

- Organisational change is complex and requires an iterative and incremental evolutionary approach.

- Don’t Copy & Paste “Best Practice”, instead emerge context specific practice through experimentation and learning.

- Establish a clarity of purpose at all levels and engage those impacting and impacted by the changes.

- A Psychologically Safe environment will enable challenges, weaknesses, waste and errors to be surfaced and addressed.

- Start from where we are with an honest and critical analysis of the current system of work with a mindset to discover, drill down and address root causes of challenges to value creation.

- Use collective workshops where stakeholders with diverse perspectives map the current context and then analyse and understand it through the lens of Scaling Principles.

- Support workshops with appropriate collaborative mapping techniques.

- Identify and prioritise options for experiments.

- “De-scale” - always consider options for reducing the complexity of the current context!

- Reduce the risk, fear and resistance to change by using small safe-to-fail experiments.

- Be prepared to make difficult and fundamental changes rather than polishing the current system of work.

- Shape, support, and incorporate learning from experiments into emergent practices.

- Scaling success should be an evolutionary process.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_adaptive_system

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OODA_loop

Set-based Concurrent Concurrent Engineering

Minimum Viable Changes (MVCs) - Little, Jason. Lean Change Management: Innovative practices for managing organizational change (p. 36).

Darley, J. M., & Batson, C. D. (1973). "From Jerusalem to Jericho": A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27(1), 100.

How to Change a Culture: Lessons From NUMMI - Shook, John https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-to-change-a-culture-lessons-from-nummi/